The Red Envelope: Billkin and PP Krit’s Take on a Love Story Beyond the Grave

In a cinematic landscape saturated with remakes, reboots and sequels, you might ...

In this column, he heads north to the Golden Triangle to explore the art at the 3rd Thailand Biennale.

Biennales are like buses. Thailand waited decades for an omnibus art festival, then five came along in 2018. The privately-run Bangkok Art Biennale (BAB) initiated the concept here, while Bangkok Biennial, Ghost and Khon Kaen Manifesto were indy ripostes. The Culture Ministry could have combined forces, but instead claimed its own national art territory for the Thailand Biennale, which plants art flags in each region. After Krabi (2018), Khorat (2020) and a Covid hiatus, it now alternates years with BAB, having opened on 10 December 2023 in Chiang Rai.

Given Bangkok’s wealth of exhibitions, you might wonder if it’s worth the schlep north to see yet more art. Its a rare chance to see Thais amid international stars (mainly Asian) among the 60 artists at the 17 sites around Chiang Rai city, or an hour’s drive away in Chiang Saen and the Golden Triangle. A further 13 independent pavilions include the Rubinah collective from Indonesia, while 62 artist’s studios are open mainly by appointment.

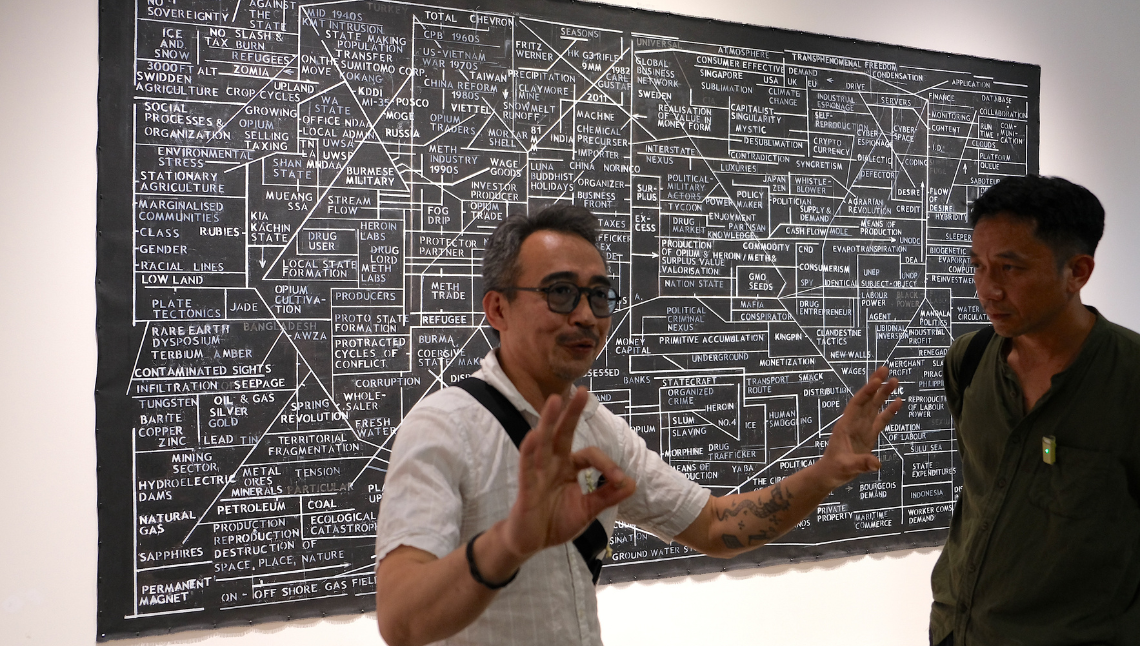

Staging biennials annually does duplicate and dilute our creative resources, but this is the most coherent Thai biennale yet, with a sense of place felt especially in the Mekong sites. The ancient walled port of Chiang Saen has its ruins augmented by several artists including Chitti Kasemkitvatana, while the museum exhibits drawings of vernacular heritage by Roongroj Paimyossak. A riverside warehouse is filled with magnificent works that tackle gnarly issues, from opium and tribal beliefs to land ownership, including a vast map that Nipan Oranniwesna meticulously made using powder.

Upstream at the Golden Triangle, Navin Rawanchaikul offers one of his community portraits on cinema banner scale. Nearby, famed Thai filmmaker and artist Apichatpong Weerasethakul projects an eyeless ghost tale in an abandoned school, and in another classroom has three motorised curtains – painted with a bucolic landscape, a blue sky, and a modern highway – jostle for dominance.

One reason that Thailand Biennale Chiang Rai (TBC) feels authentic is the local curatorial knowledge. Artistic director Gritthaya Gaweewong (of Jim Thompson Art Center) is an ethnic Yong from Chiang Saen, while curator Angrit Archariyasophon hails from Chiang Rai and ran a gallery there, while co-curator Manuporn Leungaram did research on Chiang Mai arts. Fellow artistic director Rirkrit Tiravanija lives in Chiang Mai and has just been named by Art Review as the 3rd most influential person in the global art scene (Apichatpong is 35th). Such heft drew international stars like Ernesto Neto, Thomas Rehburger and Haegue Yang.

Projections onto suspended sheets by American Sarah Sze at Chiang Rai International Art Museum.

Chiang Rai already has an artistic profile, with its top attractions being the White Temple built by the neo-traditional artist Chalermchai Kositpipat, and its ‘Black House’ counterpart Baan Dum, a complex of animistic buildings by the late painter and designer Tawan Duchanee. The White Temple hosts the TBC visitor centre and exhibits video and sculptural works by Thai wunderkind Korakrit Anunanonchai, with his trademark kinetic editing, philosophic insights and ritual burning of denim. Baan Dam exudes masculinity, yet hosts solely female artists for TBC, including Busuai Ajaw, an Akha who interprets her tribe’s beliefs onto cowhides and a winged Naga coffin.

Chiang Rai boasts a rare wealth of artists, many honoured in TBC, yet had few venues until Chalermchai’s new Chiang Rai International Art Museum (CIAM), which he sped up to host this event. Its twin pyramid-tipped towers are coloured white for him and black for Tawan. Frankly, its art is the least compelling among the major sites, aside from Sara Sze’s projections onto suspended papers, Yang’s kinetic sculptures, and Rehburger’s room of canned fish submerged into a rice field.

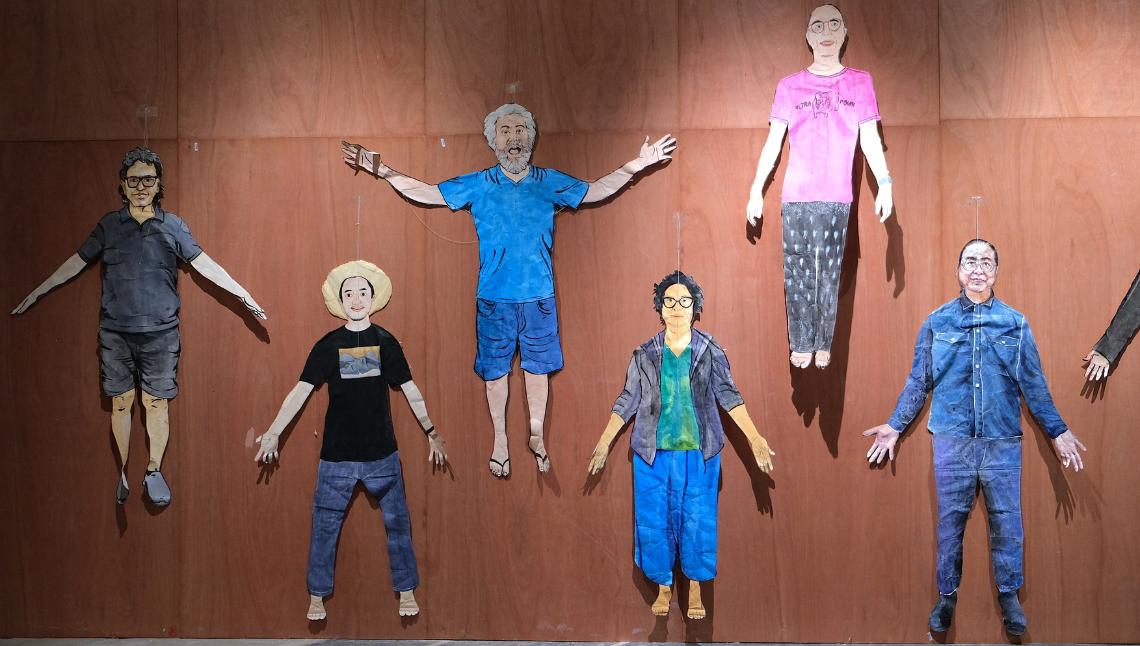

As always, there is much immersive art for audience engagement and Instagram. At CIAM, the indigenous Taiwanese Wang Wen-Chih made an egg-like bamboo pavilion where you can chill and contemplate. In Chiang Rai Tobacco Warehouse, two participatory projects will physically grow through the five-month biennale. The Argentinian, Tomás Saraceno provided instructions to build a giant balloon from recycled plastic that the public can add to or write on from inside. This “aerosolar sculpture” inflates without artificial power and slowly fills the gigantic hall, in which Shimabaku of Japan also initiated workshops for making life-size human portraits on flyable kites.

Amid rural scenery, the art gets space to breathe and impart profound meanings. Several Buddhistic structures at Cherntawan International Meditation Center leave a deep sensory impression. Arin Rungjang, a veteran of Venice Biennale, embodies folklore by cradling river and mountain rocks in red strings that splay from the roof of an oval gravel meditation path, from which also dangle bamboo chimes rung by leaves from the nearby boh tree.

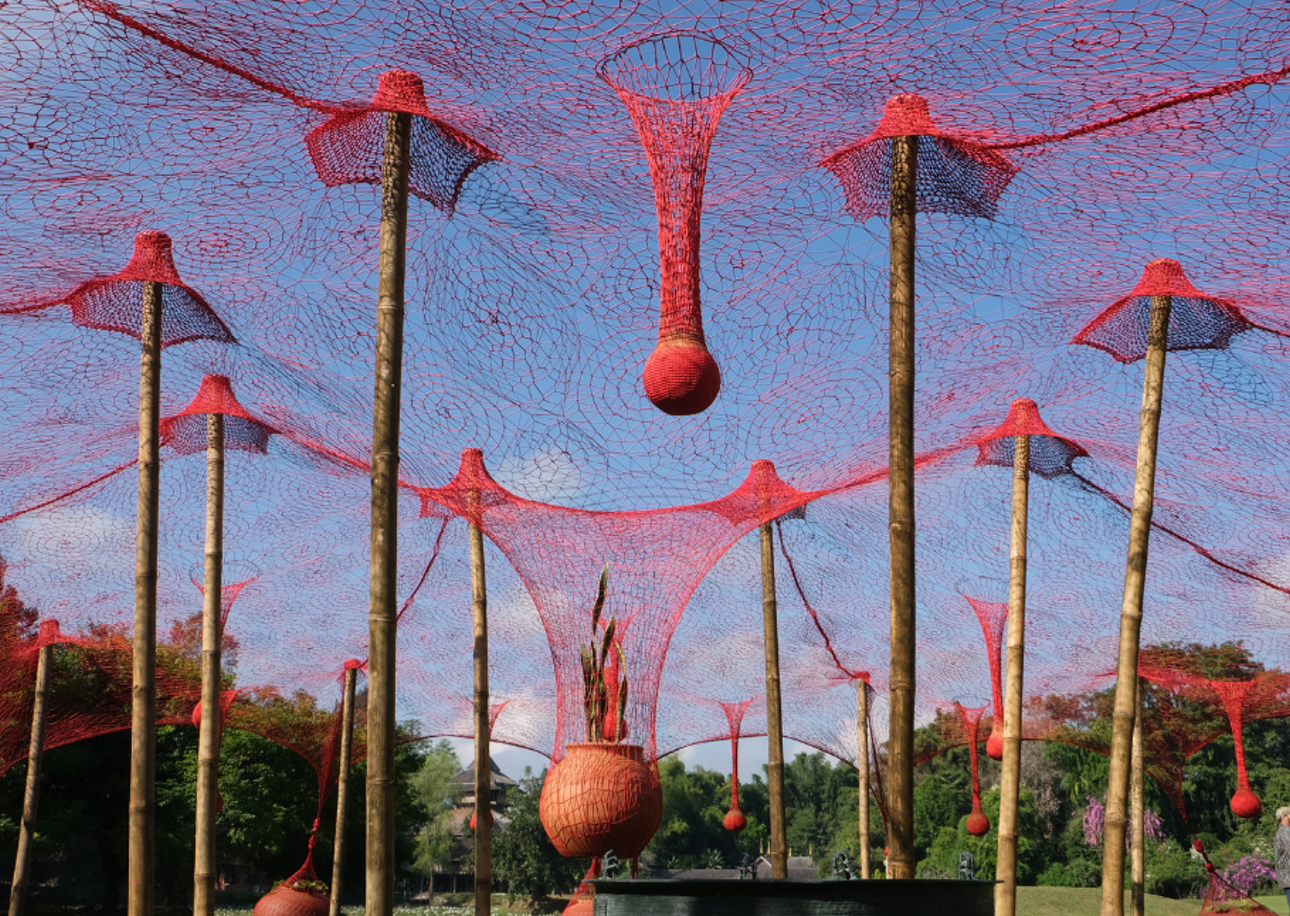

At Mae Fah Luang Art & Cultural Park, the lush botanical gardens seem to have sprouted the bamboo, clay and macrame carapace by Brazilian luminary Ernesto Neto, anchored by rain drums and fruiting with bulbous uvulae scented by herbs. Across the lotus lake, the cavernous wooden Haw Kham tower emits spellbinding sound art by Nguyen Trinh Thi of Vietnam. Automated ranat xylophone chimes and wooden pipes hidden among the Lanna artefacts sound according to changing water levels and current speeds being measured live in the Mekong.

Arin Rungjang’s installation at Cherntawan International Mediation Center.

When I toured potential Biennale sites with the curators last March, the PM 2.5 index reached 600, veiling everything including the culprits. Several artists who probe the dire effects of dams and air pollution all do it poetically, since politics is absent from this ministry-run event. Mentioning causes, corporations or China seems taboo.

Yet some things are open to interpretation. An architectural artist from Taiwan (here labelled Taipei), Michael Lin sealed the derelict former provincial hall, a hub of Bangkok’s rule, with panels of enlarged textile patterns from tribes whose distinctive cultures were marginalised by national standardisation.

Upland Asian tribes eluding state control have been labelled Zomia (meaning “Distant Peoples” in Burmese). A charming pavilion in an old missionary mansion, Zomia In The Cloud, posits art as a way to continue Zomia’s ungovernable spirit. Meanwhile, looming across the Mekong, a lurid casino enclave autonomous of Laos has been dubbed Zomia 2.0. Another edgy pavilion, by Chiang Mai gallery MAIIAM, shows bottles of illicit Shan liquor painted to depict their oppression.

Amid the flashy opening, prime minister Srettha Thavisin praised the coordination that enabled this spectacle. Roving biennales around the country seems like a bright idea, but training a provincial bureaucracy to world-class culture management standards every two years is beyond reason or resources. Wise mutterings infer TBC may stay in Chiang Rai, though whispers suggest Phuket might be next. Perhaps it should alternate between those two.

The culture minister uttered the dreaded catchphrase “soft power.” Indeed TBC could transform Chiang Rai’s global profile – and give incentives to revisit the area with fresh eyes. Part of the generous funding supplies vans to connect all sites until it closes on April 30, but better go before the smog season. Touring the main sites could take three-to-four days.

Whatever TBC’s future, it leaves a permanent legacy. CIAM will keep Somluck Pantiboon’s angular pavilion and all(zone)’s wave-roofed galleries, while Wang’s bamboo structure should last four years. Cherntwan will preserve Chata Maiwong’s gigantic assemblage spanning four tree trunks, plus the three stupas erected by Sanitas Pradittasnee: one of metal, a mirror-lined one made of soil, and a mesmerising one of mirror tiles that vanishes amid the surrounding plantation.

Perhaps the best artwork of all will remain at Mae Fah Luang Park: a 140-year-old stilted rice barn carved by Ryusuke Kido of Japan. Using dentistry drills, he etched lattices of holes across the weathered boards that evoke viral or bacterial decay, releasing the heady scent of teak oil. Whether hollowed-out heritage or a topical take on our post-pandemic scars, this Thai-Japanese hybrid embodies so many ideas in a parcel of exquisite beauty. In a grace note, you can contemplate it from the shaded hammocks slung between its ancient pillars.

This twice-monthly column, Very Thai, is syndicated by River Books, publisher of Philip Cornwel-Smith’s bestselling books Very Thai: Everyday Popular Culture and Very Bangkok: In the City of the Senses. The views expressed by the author of this column are his own and do not necessarily reflect the views of Koktail magazine.

All of the photos used in this article are credited to Philip Cornwel-Smith.

In a cinematic landscape saturated with remakes, reboots and sequels, you might ...

These top 5 barber shops in Bangkok are where gentlemen can elevate ...

Must-have gadgets for kids in the Y2K are, predictably, making a comeback ...

While traditional TV shows are serving us endless boy-meets-girl tales. Thailand has ...

Stay ahead of the curve with these three must-visit new restaurants in ...

See how Kim Steppé’s early passions, family values and entrepreneurial spirit continue ...

Wee use cookies to deliver your best experience on our website. By using our website, you consent to our cookies in accordance with our cookies policy and privacy policy