Gentlemen’s Guide: Bangkok’s 5 Best Barber Shops

These top 5 barber shops in Bangkok are where gentlemen can elevate ...

VERY THAI: Returning after a break, this column by author Philip Cornwel-Smith explores popular culture and topics related to his best-selling books Very Thai and Very Bangkok. Here he reviews the impact of the Bangkok Art Biennale on the city and the art world, after speaking at a recent biennale event.

Banner Photo: ‘Spectre System’ by Preeyageetha Dia at QSNCC

The 4th Bangkok Art Biennale (BAB4) is two-thirds of the way through its four-month run. That’s a good time to see how’s it going. Biennales aren’t neutral. They spark love or loathing, swoons or yawns, and shift how we see a place. Whatever the reaction, Biennales matter.

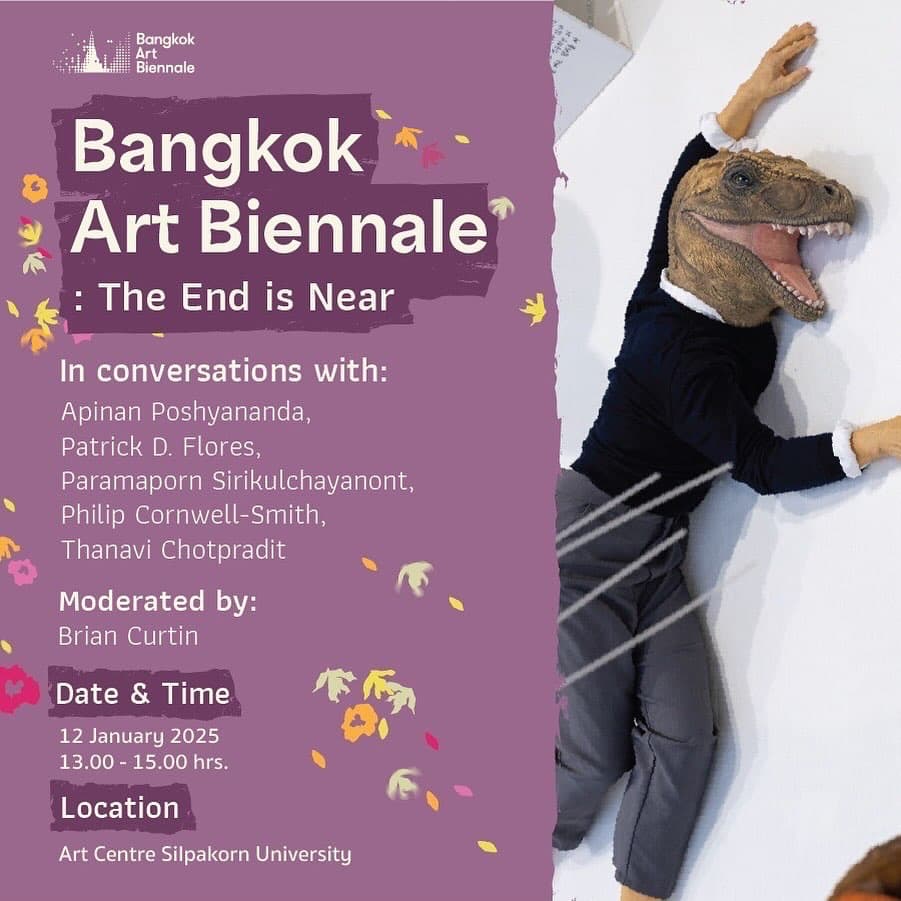

As some of the reviews were critical, BAB responded with a debate at Silpakorn University Art Center on January 12, under the teaser title: ‘The End is Near.’

In a land that can be a bubble of Thainess, BAB makes a point of hosting foreign artists, curators and pundits, whether visiting or expatriates. That was reflected in the panel of BAB founding director Apinan Poshyananda, Filipino curator of Singapore Art Museum Patrick Flores, art lecturer Thanavi Chotpradit, BAB4 curator Paramaporn Sirikulchayanont and me, moderated by BAB4 curator Brian Curtin. Among the issues tackled were sponsor influence and whether biennales remain relevant. This is my take.

In Bangkok Art Biennale, most people dwell on the “Art” bit, but my job is to focus on ”Bangkok.” This vast event impacts the city – and Thai soft power. Biennales – like the original in Venice – are typically run by a city to enhance its image. BAB has already leavened Bangkok’s reputation and self-image beyond a threshold. Stopping it would feel like dropping the ball.

Thailand came late to the biennale game, trailing Indonesia, Singapore and the Philippines. Yet BAB and new investments are propelling the city to art hub status. One ASEAN artist told me that BAB would lift them more than any previous event. An Indonesian artist wondered how his far bigger country could now compete.

Meanwhile, private complexes are mounting public art by famous artists. At OneBangkok, ThaiBev unveiled works by Tony Cragg and Anish Kapoor for BAB4 and re-situated one from BAB1 by Elmgreen & Dragset. Soft power isn’t just about things Thai, but also joining things global.

BAB attracts prominent art figures, with BAB4 having advisors from the Mori, Pompidou and Singapore museums. Yet weary pundits decry biennales over “festivalism” and the agendas of politics, commerce and host cities. Critical piety over the structural drawbacks can however pre-disqualify consideration of the artistic and curatorial merit – and the relative situation of those catching up. Given Thailand’s weak education in non-traditional culture, its art ecosystem hinges on cultivating deeper appreciation among the public, officials and collectors.

Delicate negotiations to place art in temples, museums, malls and heritage buildings have begun to mellow stuffy institutional guardians. Veterans of biennales abroad notice how BAB-goers expand beyond the usual earnest literati to throng with keen young Thais. And that very festivalism engages tourists and the masses. If only a fraction of the 775,000 who’d visited BAB displays by January 20 get inspired to enter or support the arts, that’s a win.

Popularity doesn’t always mean festivalism. There is a palpable thirst among young Thais for outside ideas that BAB helps supply. When the Institute of the performance artist Marina Abramovic – a BAB consultant – joined BAB1, participation by Thais in its austere durational disciplines was among the highest worldwide.

Wags often dismiss Instagrammers posting with cute displays like the inflatable fruits by Choi Jeong Hwa. Yet art events worldwide cater to social media for publicity and those who take selfies can be serious too. Many artists treat Insta as a portfolio, and I saw lots of them pose at BAB4 spectacles like Adel Abdessemed’s installation of three entwined aircraft.

Some works tackle edgy topics. Gallery-goers wrote on the T-shirt that Burmese dissident artist Moe Satt writhed inside to demonstrate the constraints under Myanmar’s junta. Bounpaul Phothyzan carved village scenes into giant bomb casings to show the destructions and disabilities wrought by the ordnance dropped on Laos. Taiki Sakphisit filmed a dreamscape around the French home of exiled Thai premier Pridi Banomyong. Sophirat Muangkum turned her camera lens on the taboo-laced subculture of nudism.

Apinan still sets BAB’s curatorial tone. His recipe mixes topical commentary with interactive pop arts, and global art superstars with rising Thai names. This year’s “discovery” is Supawich Weesapen for meshing digital networks with folk cosmology. A unique figure who links art to commerce and the bureaucracy, Apinan builds diplomatic bridges to tradition, showcasing late Thai and foreign masters, and involving heritage venues with aesthetic, promotional and political savvy.

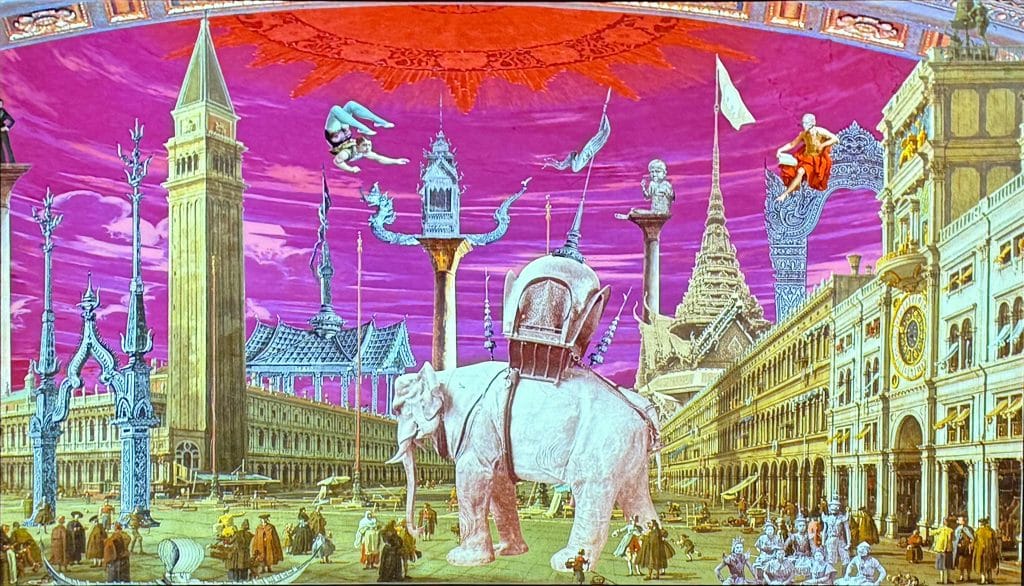

This year, he persuaded the Fine Arts Department to open its bastions of Thainess: the National Gallery and National Museum. Artists were invited to develop “conversations with artefacts” from the collection. Komkrit Theptian matches stone deities with his cute miniatures and Dusadee Huntrakul contrasts his ceramics with primaeval relics, while erotic masterpieces by French sculptor Louise Bourgeois were placed amid Hindu phalluses and yonis. This format suits the sly historicism of collagist Nakrob Moonmanas, in displays and animations at the National Museum and Wat Pho, paired with antique clocks.

BAB’s trademark is temple settings, now joined by Wat Boworn. Amid its Gothic carvings, Cole Lu of Taiwan built a classical gateway from neem wood charred to evoke the cycles of destruction and rebirth.

BAB 4 sticks closer than its predecessors to a theme. Headlined ‘Nurture Gaia,’ it alludes to both the Greek goddess Gaia and to Gaia Theory, about the interconnectedness of planetary ecology. This extends to having female:male parity among the curators and 76 artists. Apinan is the only straight male on the team. It’s not a ’Me Too’ gesture, since top Thai curators have largely been women, and the 2023 Thailand Biennale had curator parity too.

Some say the theme is too broad, yet there is repetition of the ‘earth mother’ trope. Full-figured Indian women sculpted by Revinder Reddy emanate an aura from gilding, while Filipina Agnes Arellano humanises the generic goddesses of various cultures by live-casting the pastel nudes from her own body. Motif-packed prints by Indian New Yorker Chitra Ganesh burst with feminising takes on myth and psychedelic posters, contrasting with the surreal sprite-like reveries painted by the late Princess Marsi Paribatra. Most tenderly, the Singaporean Amanda Heng – a multi-disciplinary member of the Thai-based collective Womanifesto – photographed her ailing mother in unsparing clarity as their tense relationship softened, deeply touching anyone with ageing parents.

In counterpoint, George K layers sculptures of Indian hijras (trans-women) with texts, conveying a voice of the voiceless. From Brazil, Guerreiro do Divino Amor also plays with gender norms in his operatic video allegory of Ancient Rome – one of BAB4’s three representations of the multi-breasted she-wolf myth.

Several artists allude to the eco crisis. Thailand’s Wishulada recycles waste into figures that emphasise their origin as trash. By contrast, Indonesian Ari Bayuaji disguises fishing detritus into a resource for handwoven textiles of lustrous beauty. Noting that all cultures have monsters, he re-configures the fibres from plastic ropes into deconstructed Balinese mythical creatures: a Barong lion and Rangda, a female spirit who scares humans into behaving better.

Environmental warnings also come through tech. George Bolster creates a new kind of tapestry, woven from pixels of a landscape photograph, depicting a Texan border riven by migration and the removal of nature protections by Trump. A collaboration by Bagus Pandega of Indonesia and Kei Imazu of Japan engineers a mechanical painting of a rainforest and its erasure, powered by the energy from an oil palm growing beside it in BACC. Similarly, Zul Mahmod, wires logs to function as a radio that broadcasts a ’Symphony of Coexistence.’

Briton Susan Collins set cameras on Bangkok Noi canal and the River Thames in London to relay periodic photos of the tides on screens that refresh in real time. Her similarly captured stills of the Palestinian West Bank convey the epic re-contestations of that land.

In Wat Prayoon, the media tour fell silent at twin immersive videos of American artist Jessica Segall swimming with two captive pets: an alligator and a tiger. Fed but not drugged, the beasts leave viewers gasping at the risk to her, and us, of toying with nature.

BAB also exhibits in the vast complexes of Queen Sirikit National Convention Centre and the new OneBangkok – both owned by key sponsor ThaiBev, whose label colours for Beer Chang appear in the BAB livery. In the wake of Bangkok Bank Art Prize, DTAC’s prominent MOCA, and Jim Thompson Art Centre, Thai bohemia is now getting swamped with investments by CP (Kunsthalle), Central Department Store (De-Central) and, in December, Osotspa (Dib Bangkok). These giants might muscle-out indie galleries, while some artists dread corporate caution after decades of resisting state propaganda.

Vehemence against “artwashing” by sponsors so roils the West that the boards and names of institutions have been wiped clean of patrons deemed unfit. This revokes a longstanding civil ethic, whereby the rich repaid society through benevolence to museums, from Tate to Mori, Getty to Guggenheim.

Asked if BAB had censorship, Apinan countered that they’d shown political art and allowed a BAB4 artist to critique ThaiBev, who later switched topic for artistic reasons. Paramaporn made the point that while the West lauds public funding, many Thai artists refuse anything tainted by the state. Each culture placates its own goddesses and monsters.

In the absence of purity, the imperative shifts to what works. State budgeting takes too long and political rivals change pet projects, whereas Thai arts have had longterm support from private benefactors, like Bangkok International Festival of Music & Dance. The Nation newspaper and Central department store ran film festivals and fashion weeks for decades, while the state’s versions typically imploded after two or three years.

Although Thailand Biennale finally realised its potential at Chiang Rai in 2023, the National Gallery stopped collecting decades ago, and the stalled National Art Gallery has bought new works yet languishes unfinished. The best collection of contemporary Thai art is still in the National Gallery… of Singapore.

For decades, Thai art was divided. Thais who appealed to international tastes for topical art met with indifference or scorn from defenders of ‘Thainess.’ And Thai championing of neo-traditional, hierarchical craft seemed parochial to foreign eyes. Some of the best Thai artists exhibited mostly abroad. That gulf, amplified by political rifts, has swung towards openness in both directions since the advent of Thai biennales.

Suddenly, mainstream Thais take pride in Thai artists being exhibited alongside world-renowned stars. And all of that art is of the edgier kind. At the National Gallery, vivid displays of punchy BAB artwork flank the institution’s collection by Thai modern masters, which now feels like a sepia glimpse of a bygone era.

Thailand had a pavilion at the Venice Biennale, only to be cancelled by the junta. Then last year, BAB hosted ASEAN artists at an independent Venice pavilion, ‘Spirits of Maritime Crossing.’ It earned good reviews and augurs a potential formal return.

While the state plays catch-up, the panel’s title, ’The End Is Near,’ hinted that BAB might cease. However, Apinan revealed that BAB5 is already funded. Given Thailand’s fitful record in the arts, such constancy provides something for Gaia to nurture.

This periodic column, Very Thai, is syndicated by River Books, publisher of Philip Cornwel-Smith’s bestselling books Very Thai: Everyday Popular Culture and Very Bangkok: In the City of the Senses.

The views expressed by the author of this column are his own and do not necessarily reflect the views of Koktail magazine.

These top 5 barber shops in Bangkok are where gentlemen can elevate ...

Wandering around the globe, try out the signature tastes of cultures across ...

Pets, as cherished members of our families, deserve rights and protections that ...

Sailorr and Molly Santana’s black grills fuse hip-hop swagger with homage to ...

What happens when Bangkok’s dining scene expands beyond the familiar. Ethnic border ...

The dark elegance of Frankenstein’s costume design reveals itself. Gothic and romantic ...

Wee use cookies to deliver your best experience on our website. By using our website, you consent to our cookies in accordance with our cookies policy and privacy policy