Gentlemen’s Guide: Bangkok’s 5 Best Barber Shops

These top 5 barber shops in Bangkok are where gentlemen can elevate ...

This month, triggered by an exhibition in London about the rise of cute, he directs a big-eyed gaze at the sugary cartoon mascots that accompany Thai life.

Quick quiz: how many cartoon faces did you see today?

It may be more than you realise; probably in the dozens. Aside from famous toons in comics and branded products, cutesy illustrated figures are relentlessly replacing photographed models in media and packaging, signage and phone apps.

You can hardly walk down a street or mall aisle in Bangkok without meeting a life-size fibreglass figure with giant eyes, button nose and stubby limbs who acts as a brand ambassador. Brochures and advertising are as likely to feature a digital presenter as a human celebrity. Even formal notices and warnings get dispensed by uniformed drawings far gentler than real-life officials.

Cuteness was once aimed just at children and teens. Then from the 1980s, corporations marketed ‘character products’ to young female adults, who brandished Hello Kitty knick-knacks like a badge. Computing then spread cartoons into ‘serious’ settings like commerce, education and public announcements. Now every realm of adult life feels like a branch of Barbie World.

Thai pundits recently pondered why the Siangkong community in Talad Noi represented its engineering craft with a statue of the manga character Kundum made from car parts. Toys literally R Us.

Cute is a global phenomenon with ancient roots. Mankind’s earliest visual communication was the cave-drawn ‘cartoon’ (which means ‘line-drawing’). Japanese manga comics and anime video draws from the ukiyo-e ‘floating world’ woodblock prints of Shogun-era Edo, as well as the influence of American toons on the cute characters Japan exported to eager markets like Thailand. Cute’s lineage in the West stretches through gargoyles, fairy tales and painted manuscripts to children’s books and twee Scottish pop songs.

Since the 1980s, manga has been Thais’ top reading matter and its branded character products cover everyday things, from clothes and containers to bedding and furniture. Vendors recline in Doraemon deckchairs, porters don Dragonball T-shirts, aunties wear Pokemon pyjamas to 7-Eleven. With advertising that wraps trains or buildings, Bangkokians spend much of their lives immersed in corporate cute. Understanding this phenomenon matters.

Thai beliefs underpin this affinity. Outlined imagery has Thai precursors in temple murals, stylised sculpture, and the line-drawings in Phrommachat fortune telling books and traditional lai thai pattern manuals. Thailand’s Hinduised culture has a pantheon of deities, masked dance and fantasy creatures. Saving face instills an ethic of pleasant, non-committal appearance. Buddhism’s iconography is specifically non-realist and urges detachment. Animist conjures spirits that inhabit fanciful figurines on altars in home, work and street. The sheer number of facial images in Thai surroundings is extreme in this ‘Land of Smiles.’

Thai festivals are full of cute sacred iconography. Even sculptures of monks and talismans like the nang kwak beckoning lady have morphed towards plump, smiling dolls. Spirit houses are peopled with miniature deities and dancers, servants and zebras, with the one at Bangkok’s Montien Hotel being swamped in Doraemon offerings. The latest Thai sacred tattoo imagery features a prosperity toon character called Labubu.

Having written about cute in my book Very Thai, I was keen to see the major ‘Cute’ exhibition at Somerset House in London. Incredibly, it lacked any Thai exhibits, and was thin on Asian examples aside from Japan. It wasn’t very focused, but did explore how the world is succumbing to sugary mascots.

Its heart was a huge installation about Hello Kitty, decked with a super-fan’s collection of soft toys of this expressionless cat. Cabinets displayed the sheer breadth of paraphernalia that she’s colonised, from cameras to cooking pots. Lacking a mouth and a personality, Kitty is blank face on which to project any emotion or insecurity.

The exhibition was in partnership with Sanrio, the Japanese owner of Hello Kitty, to mark the character’s 50th anniversary. Museums increasingly dilute their integrity and objectivity by favouring sponsors, here excluding rival cute brands. Among glaring absentees, the biggest Dumbo (not in) in the room was Disney, history’s greatest purveyor of cute, as well as Asterix and Tintin, Looney Tunes and Wallace & Gromit. These glaring omissions reflect the lucrative power of cute intellectual property.

While censoring many key players, the curators highlighted creativity and subcultures. Fine art is succumbing to cuteness, especially in glossy sculptures and synthetic digital art in candy colours – a zeitgeist visible in Bangkok galleries and Mango Art Fair.

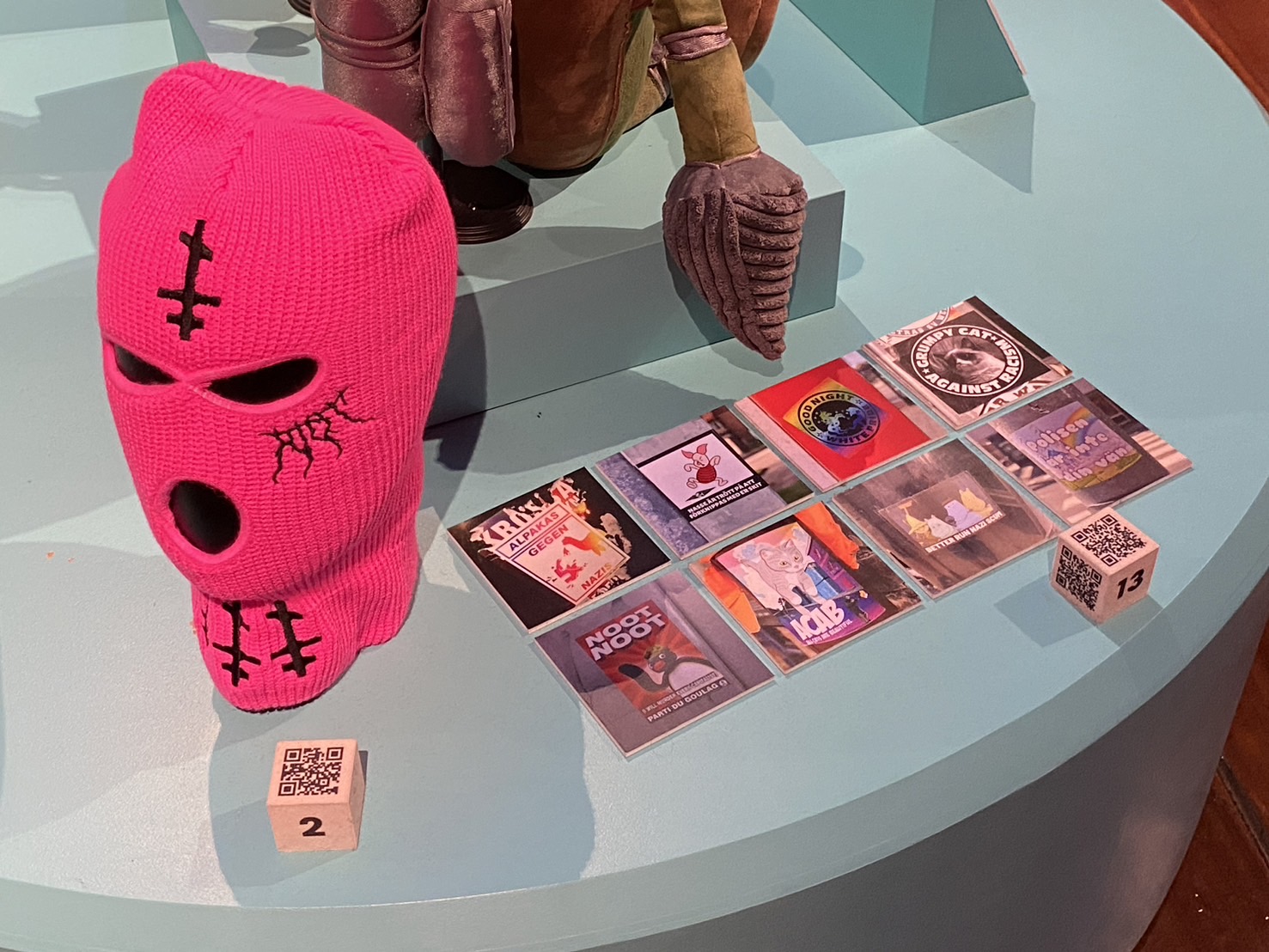

Cute’s penetration was clear in the exhibition’s breadth, being simultaneously an Instagram set for selfies, an arcade of digital games, a peepshow of kinky toons, and a gallery of mutant creatures. Families posed with cuddly toys and one display, then at the next, parents shielded their children’s eyes from nightmarish grotesques. It also documented political cute. Cuddly propaganda is beloved by dictators and subversives alike, from North Korean kitsch to Pussy Riot to rubber ducks in Thai and Hong Kong protests. It shows how deeply cute has infiltrated our lives, with serious implications.

Cute fine art at the Mango Art Fair

The dominant, most obvious view holds that cuteness indicates childishness and submission, with the technical term being “infantile biomorph.” Others suggest their ambiguity reveals a complex psychology that’s edgier, transgressive, even radical – not so much passive as passive-aggressive.

Cute is most popular in hierarchical societies and has grown in the West during a rise in authoritarianism and a loss of autonomy to digital monopolies. Humanity is slipping from a written culture back towards an image culture. Words enable fine distinctions in meaning, which enable law, democracy, science, literacy and intellectual prowess, whereas images cannot articulate precisely, disarming us from holding people accountable.

We can already see a cost of reducing complex things to simplistic mascots. Cartoons are used much like human celebrities to promote and endorse products. Yet toons don’t have ethics or independence, and can be manipulated in sinister ways. The recent Hollywood actors’ strike was partly to prevent their AI likenesses becoming owned and moulded like toons.

DIY cute in our own avatars on Facebook

We are also charmed by cute versions of ourselves in social media profiles. Emoticons can be generated from cartoonified self-portraits. Akin to assembling an Identikit picture of a criminal suspect, we pick our unblemished lip tone and eyebrow curve from a limited library in that app. Like corporations, we seek to control our public face, yet these deceptive self-edits instead conform our uniqueness to a generic copyrighted template we don’t own.

Digitised portraits get called an ‘avatar,’ a word familiar to Thais, as it’s the Indic term for an incarnation of a deity. In general, Asians seem more comfortable with cute likenesses, probably due to the longstanding extent of image curation in their ‘face’-oriented cultures. Avatars are a form of eternal life. Our cute computer avatars will outlive us, without ageing, and join Mickey Mouse, Hello Kitty and Kundum in the multiverse.

These top 5 barber shops in Bangkok are where gentlemen can elevate ...

Wandering around the globe, try out the signature tastes of cultures across ...

Pets, as cherished members of our families, deserve rights and protections that ...

Sailorr and Molly Santana’s black grills fuse hip-hop swagger with homage to ...

What happens when Bangkok’s dining scene expands beyond the familiar. Ethnic border ...

The dark elegance of Frankenstein’s costume design reveals itself. Gothic and romantic ...

Wee use cookies to deliver your best experience on our website. By using our website, you consent to our cookies in accordance with our cookies policy and privacy policy