Foodie’s Bucket List: 24 Iconic Foods to Try Before You Die

Wandering around the globe, try out the signature tastes of cultures across ...

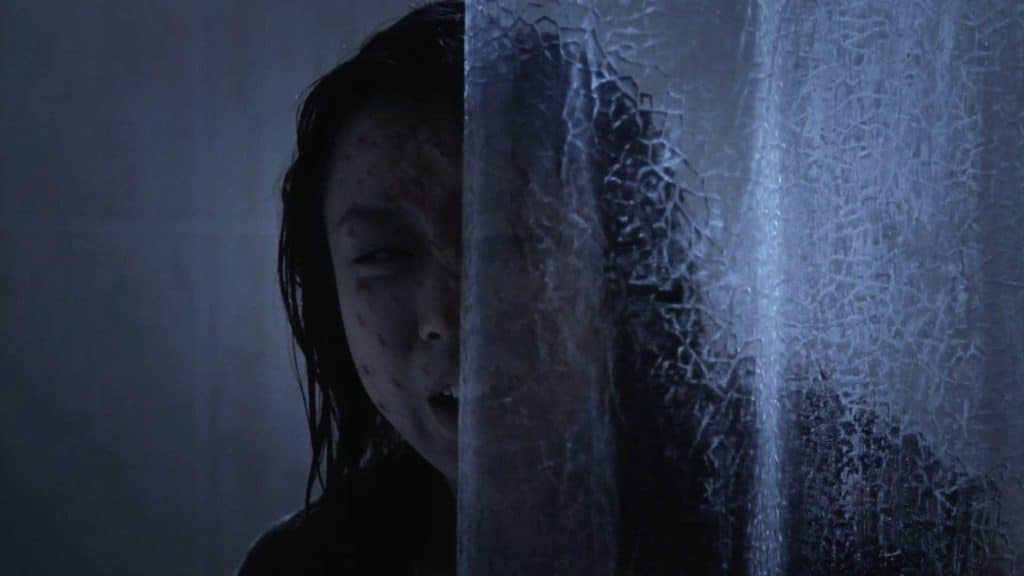

What is it about these haunting female ghosts that keeps audiences coming back for more? Let’s take a closer look at some of the Thai horror films that feature this angry female ghost archetype.

In this groundbreaking thriller, karma develops like a photograph in a darkroom. When a young photographer’s past quite literally weighs him down, audiences are treated to one of the most talked-about films in Thai cinema. Natre, our vengeful spirit, hauntingly demands accountability with the persistence of an unpaid bill. The film cleverly uses photography – typically a tool for preserving memories – as a weapon of exploitation and shame, reflecting real-world cases of image-based abuse in Thai society.

Through the story of Tun, a privileged urban photographer, and Natre, a wronged lower-middle-class student, the film exposes how class divisions, male solidarity, and institutional protection often shield perpetrators from consequences. The ghost’s physical manifestation of literally weighing down on Tun’s shoulders symbolises both the burden of guilt and the growing pressure of public accountability in modern Thai society.

When Natre was alive, her voice was silenced by a patriarchal system that protected “promising young men,” but in death, she represents the unavoidable consequence of unaddressed crimes. Through its supernatural lens, Shutter captures something all too real: the weight of silence, the privilege of power, and the persistence of justice seeking its due, no matter how long it takes.

Based on Thailand’s most beloved ghost story, this film elevates the “till death do us part” clause to new heights. Nak’s devotion to her husband transcends the mortal coil, creating a narrative where love becomes both salvation and prison. It’s less about scares and more about the devastating poetry of attachment. The image of Nak stretching her arm to unnatural lengths is undeniably chilling, but the true horror lies in the emotional and societal weight carried by her spectral return.

The film delves into deeper societal issues, reflecting the historical and political context of the time. Set against the backdrop of 19th-century Thailand, during a period marked by war and governmental instability, Nang Nak touches on the impact of such confusing and scary times on family structures. The war, which often tore families apart, serves as a commentary on how the societal forces of government and conflict can have devastating consequences on personal lives. The story of Nak and her husband, whose love is tragically interrupted by premature death, can be seen as a metaphor for the broader disintegration of familial bonds during periods of upheaval.

Additionally, the film resonates with themes of gender and societal expectations, particularly the role of women in Thai culture. Nak’s ghostly devotion raises questions about the power dynamics in relationships, where women’s love and loyalty are often framed as eternal, unquestioning, and sacrificial. Her attachment to her husband is so strong it defies death, symbolising the cultural expectation for women to sacrifice their well-being and identity for love, duty, and family—reflecting how women have historically been confined to domestic roles at the cost of their personal freedom and agency.

While not exclusively about a female ghost, this social commentary is dressed in supernatural clothing with a memorable vengeful spirit. The film delves into pressing issues such as class inequality and the breakdown of family structures in modern Thai society. The ghost serves as a haunting metaphor, reflecting deep-seated fears of displacement, isolation, and the struggle for a sense of belonging amidst rapid societal change.

Closely linked to Laddaland, the short film Makhin (2013), released as a side story, delivers a powerful critique of Thailand’s treatment of migrant workers. Through the horror genre, it exposes the brutal realities of their lives—where some get lucky, but Makhin is a chilling reminder of those who don’t.

The film tells the story of a female Myanmar housekeeper, Makhin, who returns as a vengeful spirit after being confronted with financial hardship and ultimately facing death at the hands of a man who subjected her to sexual abuse. Through her journey, the film exposes the layered vulnerabilities faced by domestic workers: financial desperation that forces them to endure abuse, limited legal protections exacerbated by gender and immigration status, and the intimate yet isolating nature of domestic work, which makes individuals like Makhin vulnerable to exploitation—highlighting the intersection of race and class.

Makhin serves as a sharp critique of Thailand’s treatment of migrant workers, using the horror genre to expose hidden systemic abuse. The middle-class Thai household becomes a microcosm of broader power dynamics, where physical spaces—such as segregated living quarters and separate eating areas—reflect the social hierarchies that entrap workers like Makhin in cycles of abuse. Her journey from a voiceless victim to a pacified spirit symbolises the silencing of migrant workers, underscoring their perpetual outsider status, even in death.

These women represent the voice of the voiceless, returning with a vengeance to right the wrongs they endured in life. The stereotypical image of long black hair and white dresses transcends mere aesthetic choices, evolving into symbols of traditional femininity reimagined as clapbacks.

In a world where women have historically been expected to be submissive and accommodating, these ghost stories provide a subversive outlet. Unfortunately, death becomes the ultimate equaliser, allowing these wronged women to transcend societal constraints and demand the justice they were denied in life—coming for it in death.

Lastly, whether the ghost girl tropes in Thai horror films are seeking revenge, justice, or simply to be understood, Thailand’s female ghosts continue to captivate, haunting both audiences and our collective consciousness. They remind us that some stories—like some spirits—refuse to rest until they’ve been heard. These films confront us with uncomfortable truths about power, justice, and the consequences of dehumanizing anyone—dead or alive. It’s not just about women but a reflection on humanity as a whole.

Wandering around the globe, try out the signature tastes of cultures across ...

Sailorr and Molly Santana’s black grills fuse hip-hop swagger with homage to ...

These top 5 barber shops in Bangkok are where gentlemen can elevate ...

Find Bangkok's most precious Indian restaurants ahead of India’s Republic Day Indian ...

Looking for something to be inspired by? Here is your guide to ...

Experience a rare live narration of Mae Nak Phra Khanong at Thailand’s oldest wooden ...

Wee use cookies to deliver your best experience on our website. By using our website, you consent to our cookies in accordance with our cookies policy and privacy policy