Gentlemen’s Guide: Bangkok’s 5 Best Barber Shops

These top 5 barber shops in Bangkok are where gentlemen can elevate ...

Pathum Thani, a mere leisurely one-hour drive from Bangkok, is known as being a Mon enclave in Thailand. The ethnic Mon from Myanmar settled here since the days of Ayutthaya to escape persecution in their own country and are known for their riverine lifestyle and Theravada Buddhist tradition. A rare example of a Mon temple is Wat Saladaeng Nua in Sam Khok District, Pathum Thani. Built in 1839, it boasts the most iconic of all Mon religious structures—a chedi—which in Mon tradition is more representative of Buddha than an image of human likeness. Locals credit a past abbot of instilling a culture that remains to this day; daily afternoon prayers in Mon dialect are attended by the community. The Hor Trai, or the Scripture Library, holds some 5,000 ancient palm leaf manuscripts that trace the history of the temple and the surrounding community. It is built hovering on pillars over a pool of water to protect the manuscripts from ants, termites and fire. The moisture also keeps the palm leaf manuscripts from drying out.

Traditional Mon-style chedi at Wat Saladaeng Nua

An open shed houses remnants of the past–boats of various sizes that were integral to the riverine lifestyle. In the old days, people would fill their boats with earthen water jars or whatever products they cared to peddle, spend a month or two travelling up or down river, then replenish their boats with other products for the return trip. Among these is a teak houseboat with carved wall panels that open up to the breeze, powered by oars the length of two men.

A teak houseboat with carved wall panels still retains its old-world beauty

Another unique feature of this temple is the local community. People look out for each other, doors are never locked, and the authenticity of the olden day lifestyle is protected. Houses are built on stilts, and many have lines drawn on the pillars indicating the water level of particular years. Flooding is an annual phenomenon, and rowboats are brought out to get around it. Under the houses you will find wagon wheels that tower over your head, boats and oars, baskets and fishing gear.

Just further along the bank of the river is Wat Song Phi Nong. It is said to have been built in 1867 by two brothers who were robbers who had made the surrounding jungle their hideout. Unknowingly, they robbed and killed an old couple who were peddling their wares by boat and had stopped nearby for the night—only to realise later that the couple were their own parents. In atonement for their grievous sin, they build this temple. The temple has two presiding Buddha images known as Luang Phor Phet and Luang Phor Ploy, both of which date back some 700 years to the Sukhothai period. Luang Phor Phet has Khmer facial features and is said to be a spiritual icon highly respected by the riverine community. Luang Phor Ploy meanwhile presides outside in a simple open structure. Its unique feature is the lack of the flame-shaped aureole.

Luang Phor Ploy without the flame-shaped aureole

A curious modern-day addition to the temple is the presence of dozens of military dolls that line the fence and the entrance to the new chapel. There is no known reason for this unique offering, but it might be a reference to the army unit that supervises the area. The chapel also features finely executed contemporary murals that show, rather than the traditional theme of the life of Buddha, the lifestyle of the surrounding Mon community.

Luang Phor Phet is surrounded by colourful modern murals depicting the riverine lifestyle

Crossing now to the other side of the river, we head towards Wat Sing in Sam Khok District. Built in 1569 during the Ayutthaya period by Mon ethnic migrants from Burma, the temple comprises four main parts: the ubosot (convocation hall), the vihara assembly hall, the funerary urn where the relics of Luang Phor Phraya Krai, a former Mon abbot of royal descent, are interred, and the 12-cornered chedi—an architectural feature that dates back to the Sukhothai period. The temple boasts not just one presiding Buddha image but four, covering each of the four compass points. Presiding in the ubosot is Luang Phor Buddha Ratanamuni, facing east. This is a beautiful example of the Ayutthaya style of Buddha images with surrounding images from the U-Thong period.

Wat Wong Phi Nong from the river

The vihara noi, or satellite assembly hall, has very unique architectural features, firstly in the curved lines of the base of the vihara symbolising a junk. The roof is lined with Chinese style red tiles, with a cantilevered overhang in front over the single entrance. Luang Phor Buddha Siri Masaen presides in the vihara, facing west.

Luang Phor Buddha Siri Masaen in the vihara noi

Two more Buddha images are housed in the Sala Din, an open-sided pavilion that is also over 300 years old. Luang Phor To, a gold Ayutthaya Buddha faces north, while right behind is Luang Phor Phet, a reclining Buddha. Between the two images is an arched panel with the oldest mural in Pathum Thani. Now only faintly visible, it shows Buddha descending from Tavatimsa Heaven.

If you’re lucky and visit the temple in March during the annual merit-making ceremony, you will also be able to apply gold leaf to the Buddha’s Footprint which is usually safeguarded in the temple museum. Made of teak and also dating back over 300 years, the footprint is said to be framed by a bedstead that was once slept in by King Rama II on one of his visits to Sam Khok.

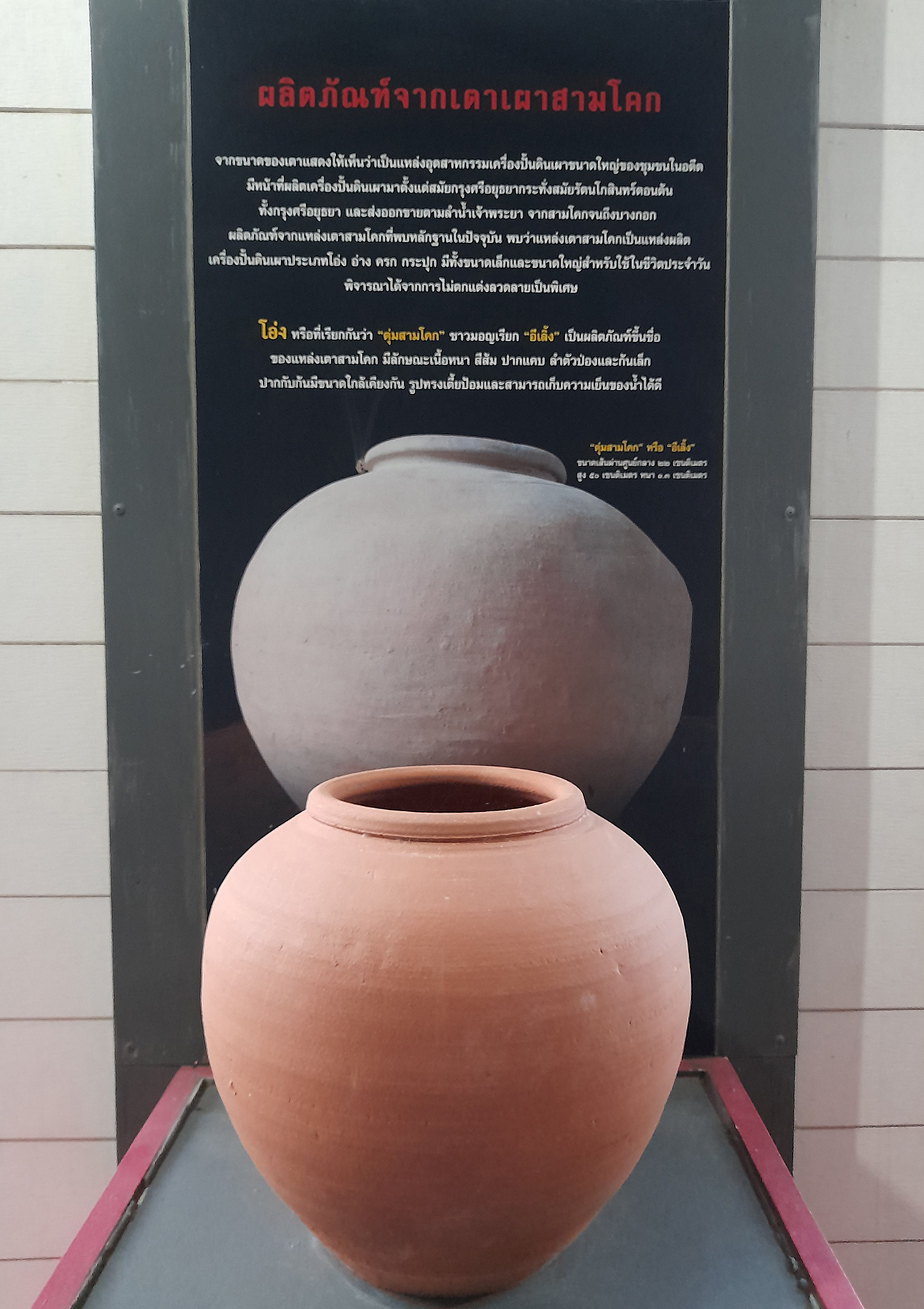

Finally, just a stone’s throw away from the temple, is the site of the old kilns, on which the district of Sam Khok is named. The Mon people were well known for their red clay pottery using river clay, as well as their red bricks which in Thai, is still referred to as ith Mon. Based in an area prone to floods, the kilns had to be built into three, high, artificially-created mounds of earth, or sam khok. Protected by a roof, the kilns are extremely large and would have been able to fire up to 200 large water jars at a time. Signs explain the process of firing the pots, as well as examples of the traditional Sam Khok red riverine clay pottery are on display for visitors, giving an insight into the cultural heart of this ancient community.

These top 5 barber shops in Bangkok are where gentlemen can elevate ...

Wandering around the globe, try out the signature tastes of cultures across ...

We asked Thai actresses and got real stars, fictional heroes and everything ...

Pets, as cherished members of our families, deserve rights and protections that ...

Sailorr and Molly Santana’s black grills fuse hip-hop swagger with homage to ...

VERY THAI: In this regular column, author Philip Cornwel-Smith explores popular culture and topics ...

Wee use cookies to deliver your best experience on our website. By using our website, you consent to our cookies in accordance with our cookies policy and privacy policy