Gentlemen’s Guide: Bangkok’s 5 Best Barber Shops

These top 5 barber shops in Bangkok are where gentlemen can elevate ...

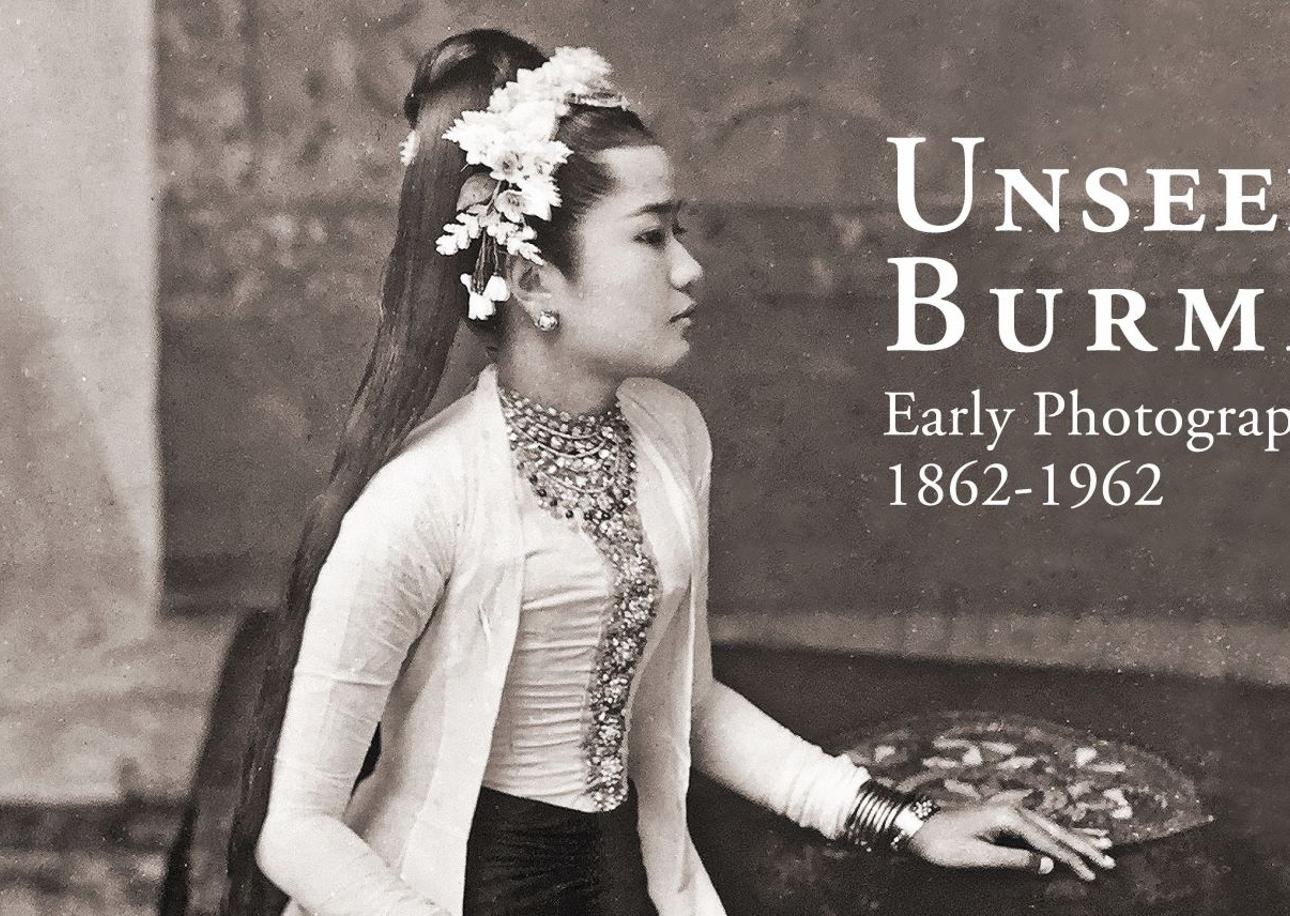

An exciting new tome from River Books is Unseen Burma by The Future List’s own Thweep Rittinaphakorn, or Ake, a highly-regarded expert on Burmese textiles and decorative art. Through his collection of old photographs, Thweep takes us into the untold history of colonial and post-colonial Burma.

Thweep began collecting old photographs to find references on how those textiles were worn by the local Burmese of old. Over 17 years, his photograph collection grew, amassed from his journeys in Myanmar as well as antique shops around Europe. Interestingly, more of his collection were sourced from overseas, since a lot of the colonial period portraits were taken by European officials for political reference.

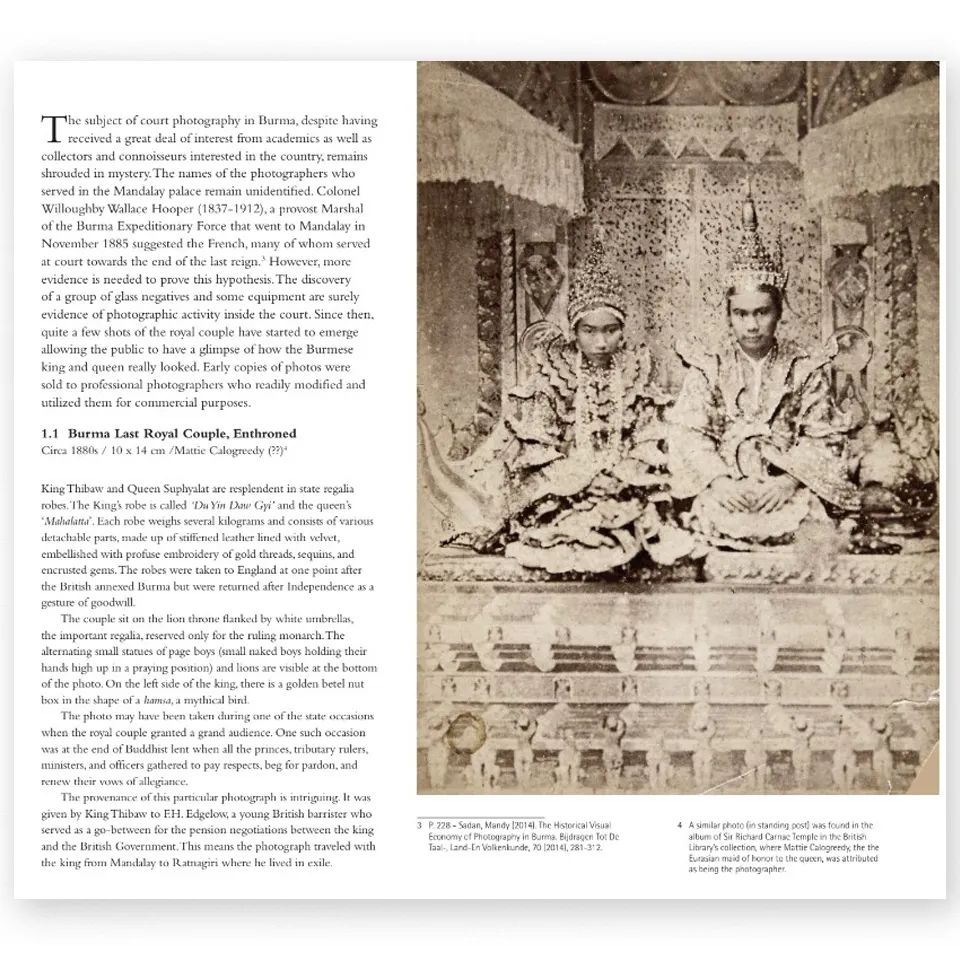

Burma’s last royal couple, enthroned. All pictures courtesy of River Books.

Like in many Asian countries, there was a certain taboo about replicating one’s image in old Burma, particularly in the royal court, resulting in a sparce availability of photographs. Thweep is therefore extremely fortunate to come into possession of a photograph of Burma’s last royal couple, King Thibaw and Queen Suphyalat from the 1880s, resplendent in their state regalia robes. According to the caption, the photo was gifted to a British barrister who represented the British government after the king was exiled to Ratnagiri, India.

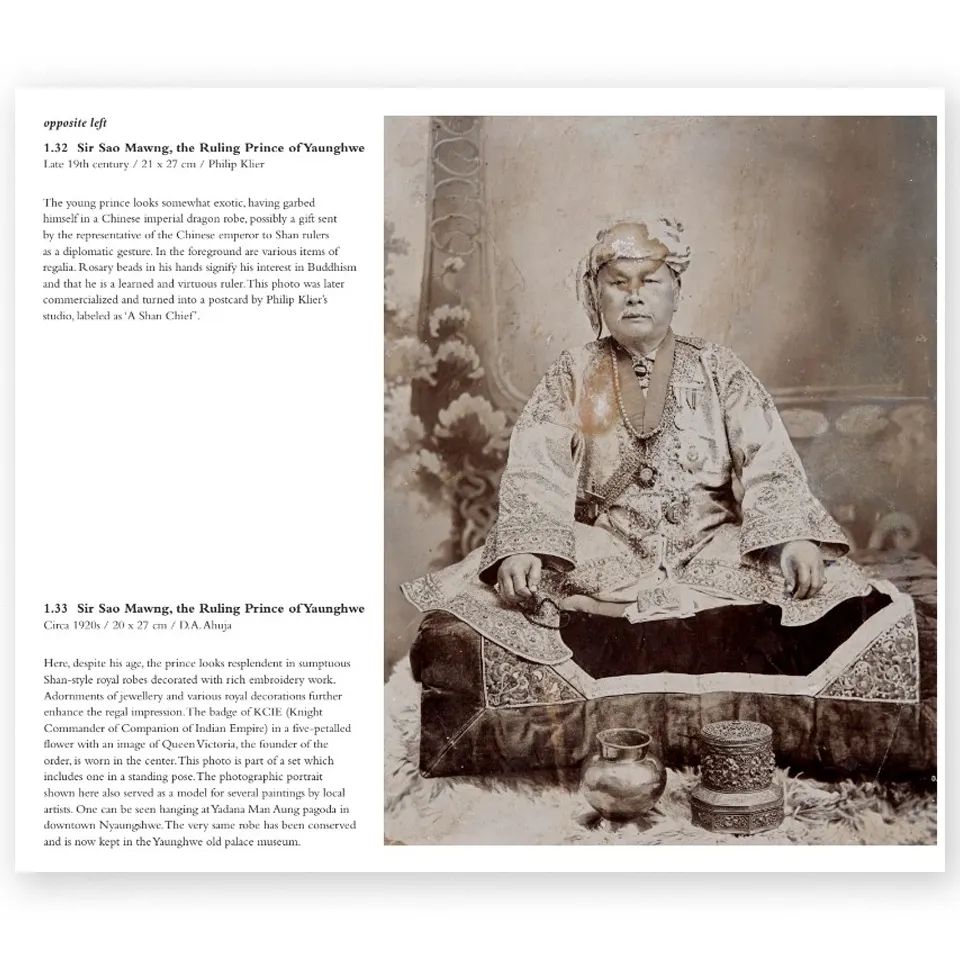

Sir Sao Mawng, the Ruling Prince of Yawnghwe.

The detailed captions are part of what makes the book fascinating. To satisfy his own curiosity in finding out as much he could about the pictures, Thweep embarked upon his mission much like a sleuth, conducting research into the country’s anthropological as well as socio-economic backgrounds, reading countless books, talking to local Burmese experts as well as experts in western institutions like the Victorian and Albert Museum in London. The captions are therefore a form of story-telling, a “show-and-tell” odyssey that draws readers into the images like a family album.

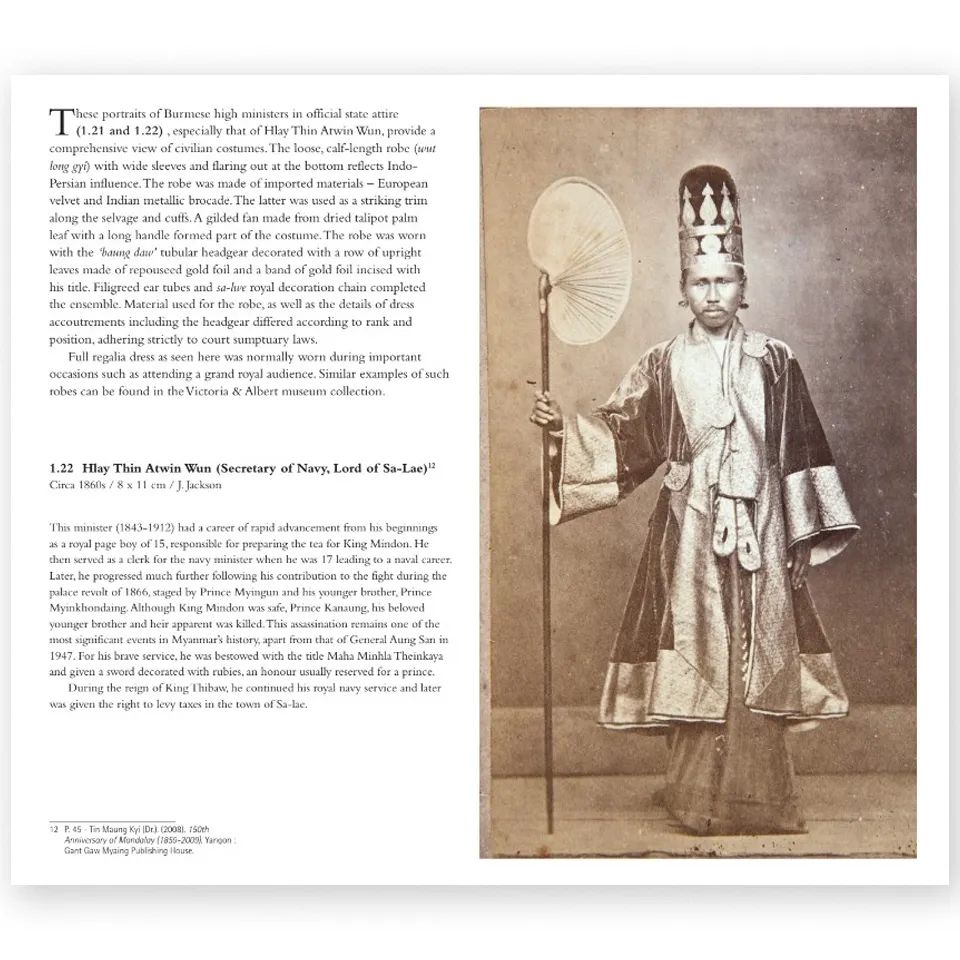

Hlay Thin Atwin Wun (Secretary of Navy, Lord of Sa-Lae)

Thweep decided to use the year 1962—the year of the Burmese coup d’etat which overthrew the civilian government under prime minister U Nu—as the starting point, and go back a century, to the days of colonialism, moving towards the age of tourism and independence. Since the photos were taken not only by Europeans officials or travellers, or well-choreographed studio portraits, but also those by local Burmese photographers when commercial cameras and film made photography more accessible and affordable, the book offers a multi-perspective into the social and historical overview of the country in a way that no other book on Myanmar has ever achieved before. It provides a true legacy of the country’s cultural and social heritage for the younger generations in Myanmar.

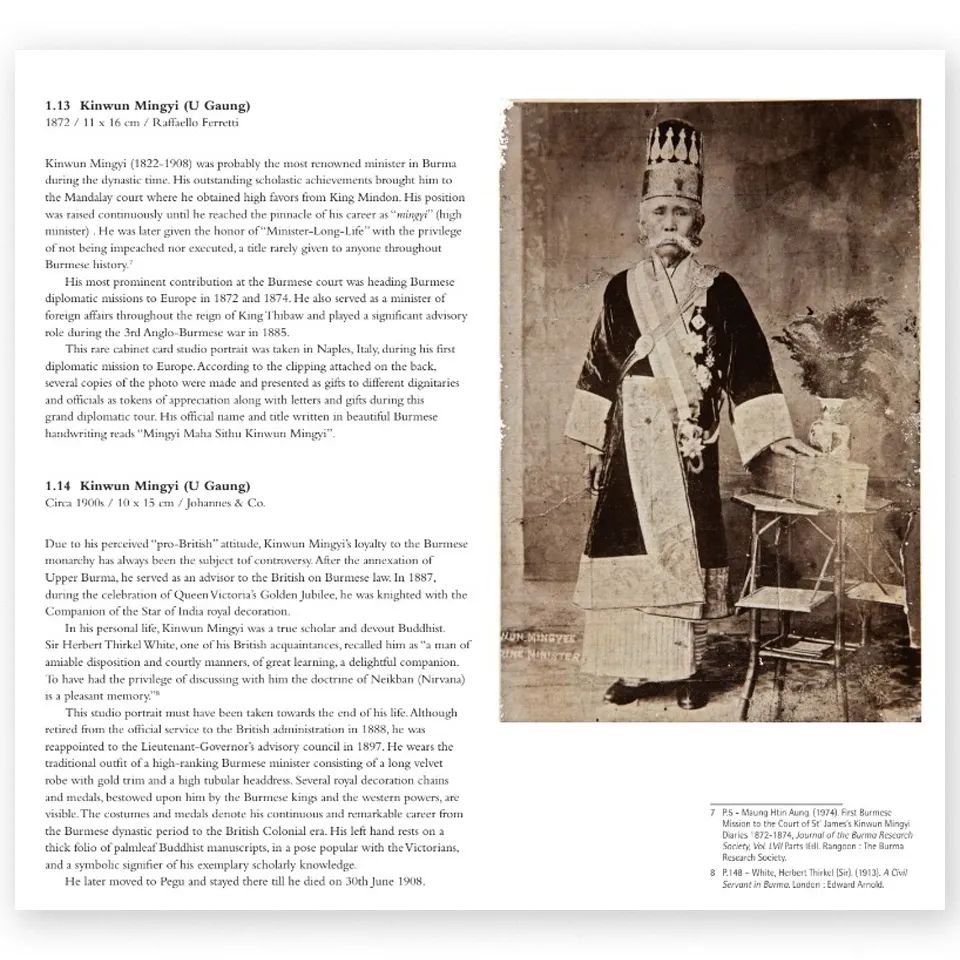

The scholar Kinwun Mingyi (U Gaung) who advised the British on Burmese law.

Among these rare images are images of royal court ladies in their elaborate attire, so magnificently structured and 3-dimensional, with gilded and sequined appendages all around that made sitting down practically impossible. There is an image of the secondary Lion Throne—the main Lion Throne from Mandalay Palace was destroyed in WWII bombing raids. Seated in front of the Lion Throne—highly symbolic in its aura of power and authority—are Sao Shwe Thaik, Myanmar’s first president, entertaining the Aga Khan.

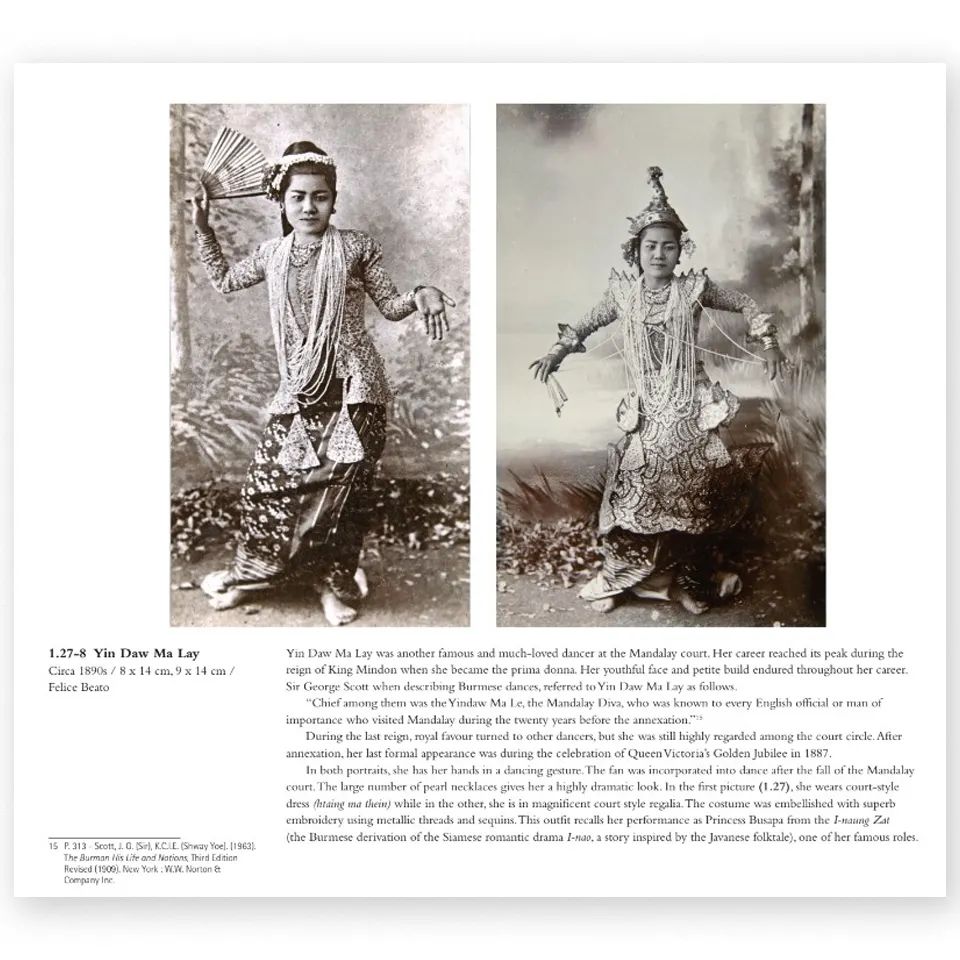

Yin Daw Ma Lay, dancer at the Mandalay royal court.

There are images of the wooden monastery in Mandalay, most of which were destroyed during the bombing raids, and the Royal Barge.

More evocative portraitures include a photo of Gregory Peck with Austrian-Burmese actress Win Min Than from the film The Purple Plain, a young Caucasian boy in Burmese costume, foreigners at a hillside military camp that could have been a scene from Downtown Abbey, and a series of local wedding photographs.

“Unseen Burma” is published by River Books, and retails at Baht 1,650.

These top 5 barber shops in Bangkok are where gentlemen can elevate ...

Wandering around the globe, try out the signature tastes of cultures across ...

Pets, as cherished members of our families, deserve rights and protections that ...

Sailorr and Molly Santana’s black grills fuse hip-hop swagger with homage to ...

What happens when Bangkok’s dining scene expands beyond the familiar. Ethnic border ...

The dark elegance of Frankenstein’s costume design reveals itself. Gothic and romantic ...

Wee use cookies to deliver your best experience on our website. By using our website, you consent to our cookies in accordance with our cookies policy and privacy policy